The rising cost of weather-related natural disasters is often attributed to global climate change. This view is wrong, says Professor John McAneney of Risk Frontiers.

It is a widely held view that anthropogenic climate change is already increasing the cost of natural disasters. Unfortunately, this is a view that seems to be strengthening despite the growing weight of evidence to the contrary.

What is undeniable is that the economic cost of natural disasters is rising, but it is doing so mostly because of growing concentrations of population and wealth in disaster-prone regions. The evidence for this is now overwhelming:

Increasing exposure of people and economic assets has been the major cause of long-term increases in economic losses from weather- and climate-related disasters (high confidence) (IPCC AR5, 2014).

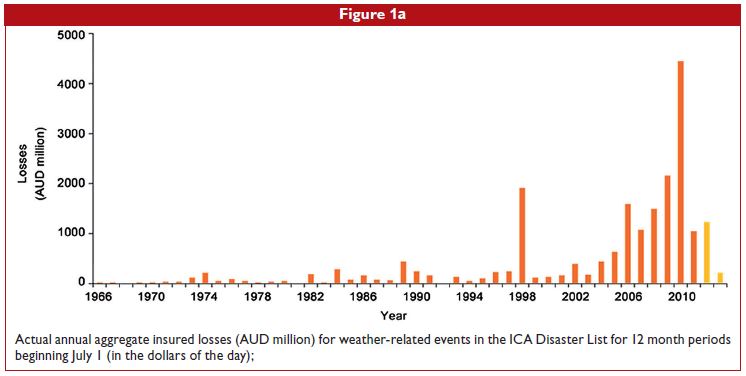

Figure 1b shows just one of the many examples of normalised loss histories that underpin the IPCC’s conclusion. The original losses are shown in Figure 1a.

Looking at losses over the years

Normalisation is a methodology used to estimate losses as if historical disaster events were to recur today under current societal conditions. The data are derived from the Insurance Council of Australia’s Disaster List (http://www.insurancecouncil.com.au/) of national insurance sector losses for weather-related disasters and have been normalised by Ryan Crompton of Risk Frontiers to 2011-12 societal conditions. The last two seasons’ data have not been normalised but this does not make a material difference to the pattern of losses.

(The original losses (Figure 1a) were adjusted for changes in dwelling numbers and nominal dwelling values (excluding land value) since the time of the original event. An additional adjustment for tropical cyclone losses was employed to account for improvements in construction standards mandated for new construction in tropical cyclone-prone parts of the country.)

Figure 1b exhibits a lot of year-to-year and decadal variance but no long-term trend is evident. In the case of the 2012/13 summer when air temperatures across Australia were at record high levels, industry losses for that financial year, which encompasses the so-called “Angry Summer”, were very close to the long-term average normalised loss of ~AUD 1.1 billion (US$952 million).

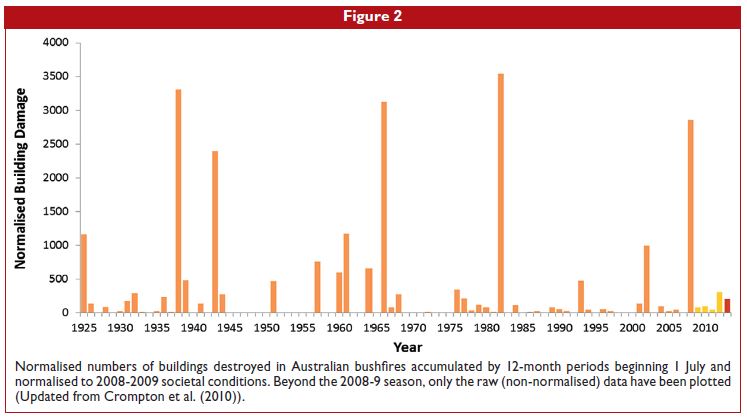

And just in case you feel that bushfires (wildfires) might tell a different story, Figure 2 shows the history of normalised building losses in Australia since 1926, the first large bushfire loss event of last century. Again we see no residual trend in the normalised losses and, like many other disaster loss histories, much of the accumulated destruction happened in just a few particularly severe events.

Link between cost of natural disasters and warmer air temperatures ill-informed

Let’s step back a bit now and be absolutely clear that by what we mean by “weather – and climate-related disasters”.

We do not mean high air temperatures, rising sea levels or long droughts, even though all of these are important. In fact, recent research at Risk Frontiers has shown that leaving aside pandemics, heatwaves have been instrumental in killing more Australians since 1900 than all other natural hazards combined (Coates et al., 2014).

What we are concerned with here are perils that can result in large-scale insurable damage. In other words, extreme weather events like typhoons, storms, tornados, bushfires and floods.

And this is not to say that global climate change does not present a problem or that we should shrink from dealing with it. Rather, it is the oft-alleged linkage between the cost of natural disasters and warmer air temperatures by climate change activists that this author finds ill-informed and misguided.

Ill informed because it is not supported by the evidence, and misguided because it is likely to lead us down wrong paths. If policy initiatives are based on erroneous assumptions, the likely outcome will be bad policy.

Hurricane “drought”

To further make the point, consider the US hurricane record. Notwithstanding the havoc caused by Super-Storm Sandy in 2011, we have now gone nine full seasons without a hurricane of Category 3 or above making landfall. This is the longest hurricane “drought” certainly since 1900, and maybe longer.

Now imagine that instead of this relatively benign period, we had experienced nine hyperactive US hurricane seasons with large insurance and economic losses. It is almost certain that if this had been the case then many climate change activists would be strongly asserting that the increased activity and the associated losses were prime facie evidence of climate warming.

Accumulation of wealth in prone areas the key reason for disaster damage

In a new book available this month, Roger Pielke Jr (2014) summarises much of the literature on normalised disaster losses and spells out the implications for public policy.

And for insurers, the absence of a signal in the disaster loss data does not mean that we should not be vigilant or that there is not a lot more bad stuff out there: remember Hurricane Andrew hitting Florida in 1992 with disastrous impact, during what had been a relatively inactive season.

So looking to the future, does climate change represent a material threat to the insurance sector?

Certainly Barthel and Neumayer (2012) after summarising their own normalised results and those of other studies, had no doubts that:

Climate change neither is nor should be the main concern for the insurance industry. Accumulation of wealth in disaster prone areas is and will always remain by far the most important driver of future economic disaster damage.

It is hard to be more unequivocal!

Business as usual: Risk assessment and prudent underwriting

Insurers have to accept the intrinsic uncertainty about the future trajectory of climate change and put more focus on the here and now. In other words it comes back to business-as-usual: risk assessment and prudent underwriting. Boring but true.

What this uncertainty surrounding climate change does do, however, is to strengthen the case for increased investment in disaster risk reduction both in its own right, and as part of adapting to an uncertain future. This is true everywhere but it is a particularly an issue across SE Asia where demographic growth is so strong and nowhere is risk-free.

Risk-informed land-use planning practices, better building codes and defence measures such as flood levees are the key to building more resilient communities. Without such efforts the cost of natural disasters will surely continue to rise.

Insurers have the safeguard of being able to update their view of risk every one to two years, and so climate change should not be their main concern. What is important is that underwriters understand company exposures, and price risks accordingly. Over time, good underwriting practices can send a powerful message to governments and homeowners to encourage risk-reducing behaviours.

Professor John McAneney is the Managing Director of Risk Frontiers. He is also the author of two books: Where Wine Flows like Water: A gastronomic pilgrimage through Spain, and a crime novel called Shifting Sands. Both are available at www.amazon.com